What in the world is a neo-cypherpunk?

Examining a new digital ideology

Hi! It’s Lucy. In November, I attended Devconnect in Argentina on a scholarship from the Ethereum Foundation. In among the tango, yerba mate, and capybaras was a group of coders trying to change the world. Below, I explore one of the ideas that has been gnawing at me since I returned to rainy London.

Hanging out with the neo-cypherpunks

By Lucy Harley-McKeown

On a blustery Sunday morning in November, I found myself in a nightclub in Buenos Aires called Deseo. Well-known for hosting frenetic electronica shows, I was there for a more sedate but potentially just as subversive gathering: the Cypherpunk Congress, a prelude to Ethereum’s flagship conference Devconnect.

As black-t-shirted coders and crypto fanatics queued to get in, volunteers were hurriedly setting up inside, plastering posters on the wall: “PRIVACY IS A CELEBRATION,” read one of them. “BREAKING TRIBALISM,” read another. “PRIVACY UNITED.”

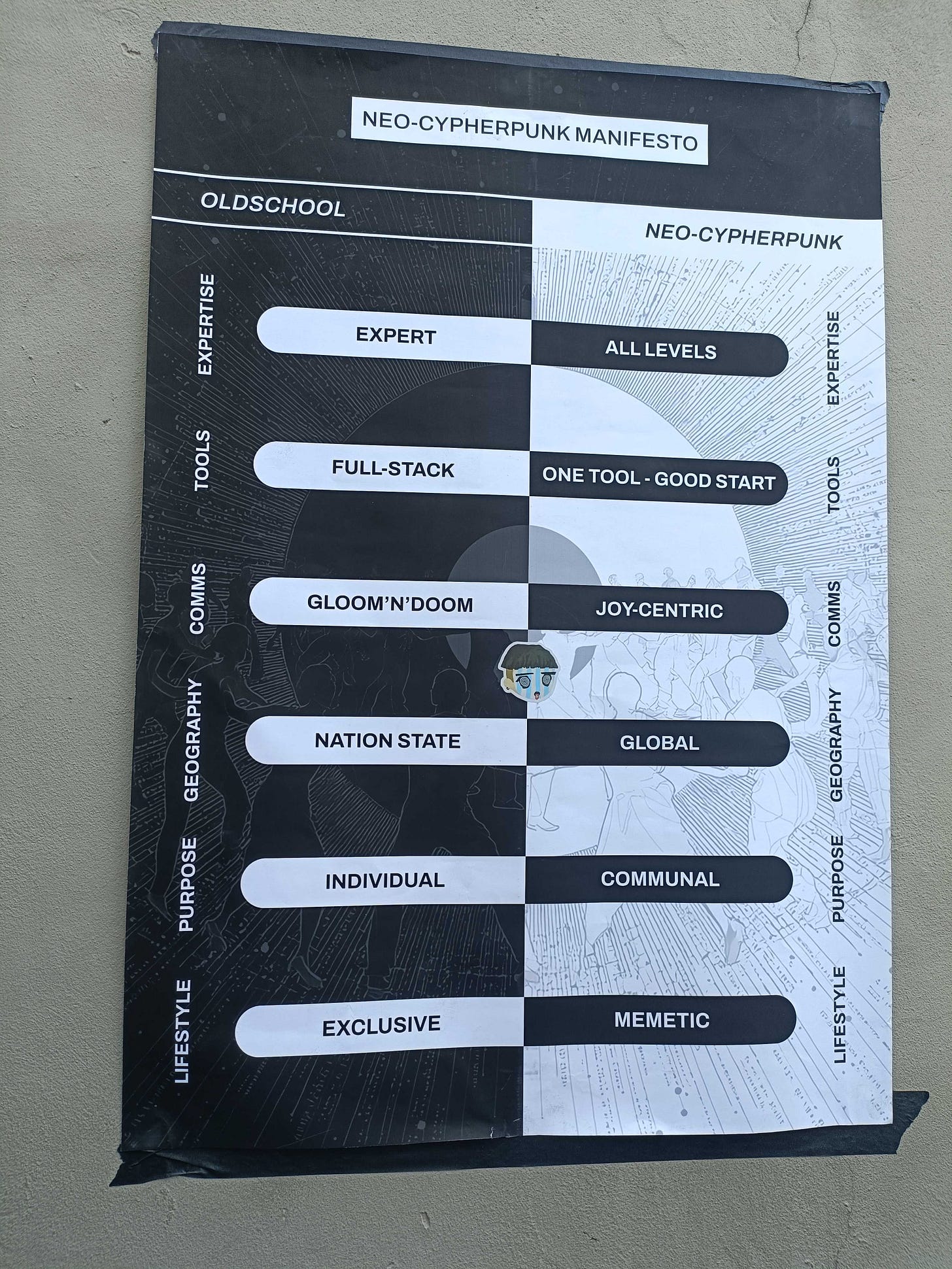

But one poster, with the heading “Neo-cypherpunk Manifesto,” stood out. What in the world is a neo-cypherpunk? As I would learn throughout the day, the term is part of a blockchain-themed attempt to reboot a decades-old idea about privacy, human rights, and technology.

The congress’s organizers hope that, in time, it will be an evolution of the roadmap for programmers set out in 1993 in Eric Hughes’ A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto. Hughes’ original essay, often cited by cryptocurrency enthusiasts, argued that privacy is essential for an open society in the digital age. Cryptographers who identified as cypherpunks were instrumental in creating private, secure, censorship-resistant communications tools and systems. These included the development of the foundations for public key cryptography, which is used by platforms like WhatsApp to keep messages private, as well as the code that became the basis for transport layer security (TLS), which keeps things like emails safe from viewers other than the intended recipients. Cypherpunks also set up bespoke systems like their own email servers and private infrastructure for communicating via mailing list. It was part of an ethos that any compromises on privacy constitute dangerous steps toward handing control of digital systems to powerful companies and governments, which are likely to use them for profit, censorship, and oppression.

This worldview was the primordial soup from which cryptocurrency emerged. Cypherpunks long desired their own digital money system separate from centralized control. Bitcoin achieved this, but it also came with its own privacy problem: the ledgers at the heart of Bitcoin and Ethereum broadcast every transaction to the public, making it possible to identify users and follow the money.

In cypherpunk form, crypto developers attacked this problem with new technology, first with Zcash, which can use zero-knowledge proofs to keep transaction data secret. Then came Tornado Cash, which uses similar technology and runs on Ethereum. Things took a dark turn, however, when North Korean state-sponsored hackers started using Tornado Cash. Two of the protocol’s developers have been sentenced to prison as a result.

The fear of prosecution has demoralized the developers of blockchain privacy tools and chilled development. The events have also reinforced a wide-reaching perception outside of the crypto bubble that blockchains are mostly used by criminals.

Behind the term neo-cypherpunk is the idea that these unfortunate circumstances do not necessarily represent a dead end. Instead of “doom’n’gloom” neo-cypherpunks are “joy-centric,” the manifesto poster read.

The pitch was to “re-boot [the] cypherpunk narrative: refresh it from ‘founding fathers bias’” but also to “accept reality,” organizer and representative of crypto education nonprofit Web3 Privacy Now, Mykola Siusko said. The event aimed to help figure out how to move beyond ideological purity in order to make the values of the original cypherpunks more malleable and “acceptable to newcomers.” The reframing was in service of building digital systems that work better for everyone. Instead of “individual,” as the original cypherpunks may have been in the early days of the internet, the new movement is “communal.”

But the crowd was full of people who have first-hand experience with the kind of optimism implicit in Hughes’s ideas curdling into wariness and distrust of the powerful institutions that oversee modern digital life. To inspire actual change, the trick was going to be doing something that crypto has largely, so far, not achieved itself: to go beyond its own echo chamber and make the case that some of these tools are useful beyond speculation and, well, crime.

The freedom to NOT swim in a dirty lake

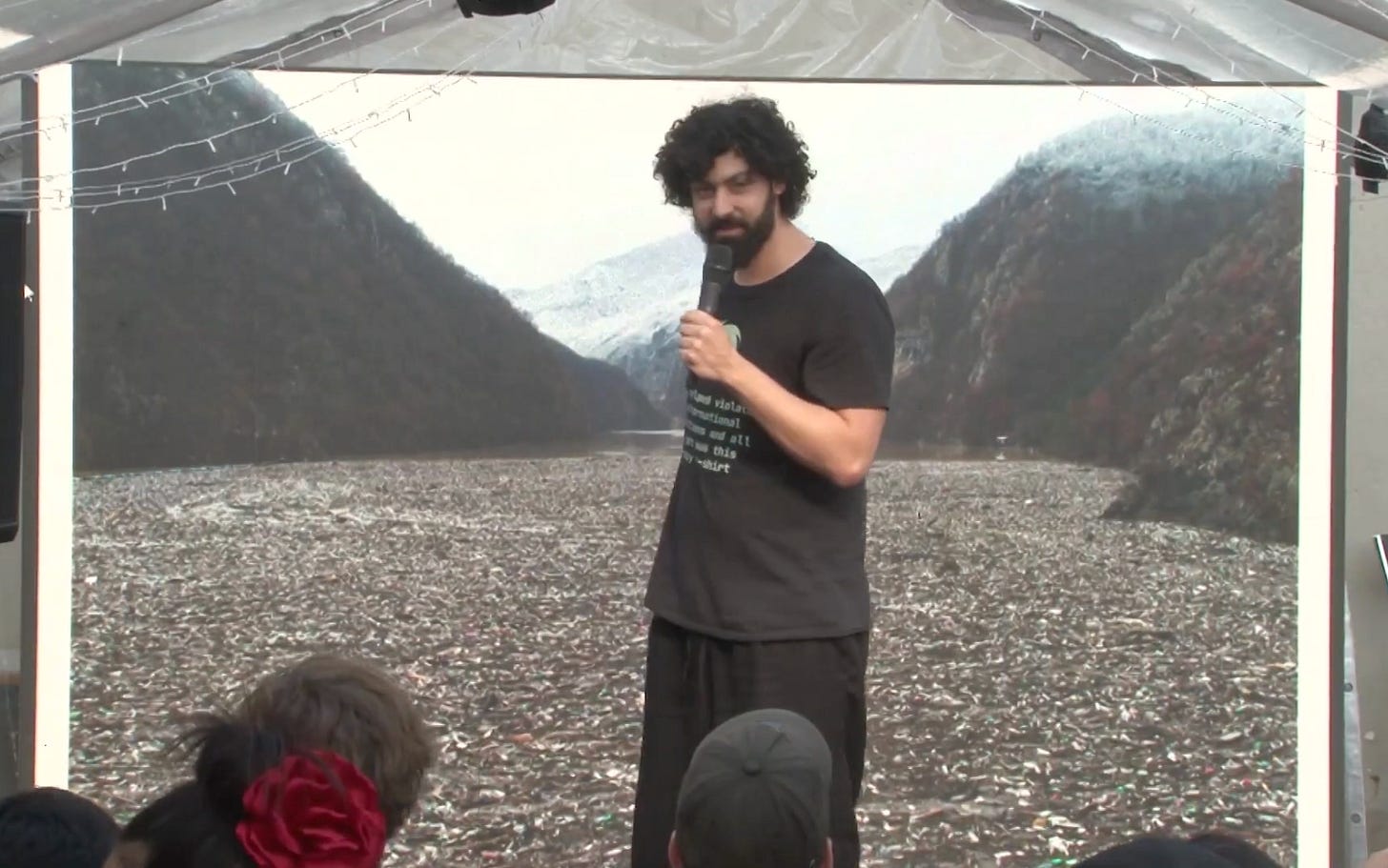

Few embody this mindset shift better than Ameen Soleimani. The Ethereum OG has been supportive of Tornado Cash since before it was built, and has been among the most vocal advocates for developers Roman Storm and Alexey Pertsev amid their prosecutions in the US and the Netherlands, respectively. Currently the CTO and founder of 0xbow, which uses zero-knowledge cryptography to achieve both privacy and legal compliance, Soleimani explained what 0xbow is building with a metaphor.

Imagine swimming in a pure, clear Patagonian lake, he said on stage. The lake is a digital space that you might like to spend time in, like a blockchain where you can transact freely and privately with others. The problem is that bad actors—including really bad actors like North Korea’s Lazarus Group—love privacy too. In Soleimani’s metaphor, Lazarus and others who take advantage of private blockchains to launder stolen funds are dumping rubbish in the lake. Anyone who keeps swimming in it gets covered in muck, and innocent people become guilty by association.

0xBow’s flagship product, Privacy Pools, is meant to keep the waters clean. The protocol uses zero-knowledge proofs to allow people to anonymize their transactions while so-called association set providers (ASPs) maintain a list of legitimate addresses that are allowed to participate in the pool, thus filtering out unwelcome actors before they’ve had a chance to participate.

The product’s inception was a response to the plight of the Tornado Cash developers. “Terrorism is, unfortunately, real,” Soleimani said, but “developers should not be held liable for the crimes of their users.”

Privacy Pools asks for a compromise: prove your funds come from a legitimate source, and you can add them to a pool that enables private financial transactions. In theory, everyone in the pool has been vetted to make sure neither they nor their money has been associated with any shady dealing.

For some cypherpunks, this idea is heresy. Any hint of attestations or proofs feels like a slide toward having to ask a centralized entity for permission. But the alternative is insisting that everyone swim in a polluted pool and risk being associated with the rubbish, Soleimani argued. You can’t demand freedom while refusing to deal with the consequences of how others use the same tools, he said. “I don’t want to be in the same association set as terrorists.”

Deciding who is a good guy and who is a bad guy is far from that straightforward, and there’s no denying this is the sort of thing cypherpunk tools—including cryptocurrency—were invented to help bypass. But Soleimani’s larger argument has to be confronted as well: treating any compromise as betrayal pressures people to cling to tools that offer fully private transactions but wouldn’t survive a regulatory or legal stress test, and might mean unsuspecting developers end up behind bars.

As such, Soleimani wants to give users a new kind of freedom: to swim in clean water and to disassociate from polluters.

Money for nothing?

There was more than one source of tension in the nightclub that Sunday. Hughes’s manifesto advocated for “anonymous transaction systems” for the internet as a whole. But the jury is still out as to whether blockchains will demonstrate they have a true utility beyond facilitating finance and profit-making.

Ethereum co-creator Vitalik Buterin has long been conscious of this. In 2023, Buterin published an essay entitled “Make Ethereum Cypherpunk Again.” He argued that Ethereum was always meant to be cypherpunk—open digital infrastructure to be used not just for payments, but as a “shared hard drive” for the internet that anyone could use. At the time, he argued the project had, in part, lost its way. With the DeFi boom and the advent of NFT trading culture, demand for speculative financial investments had taken over the network.

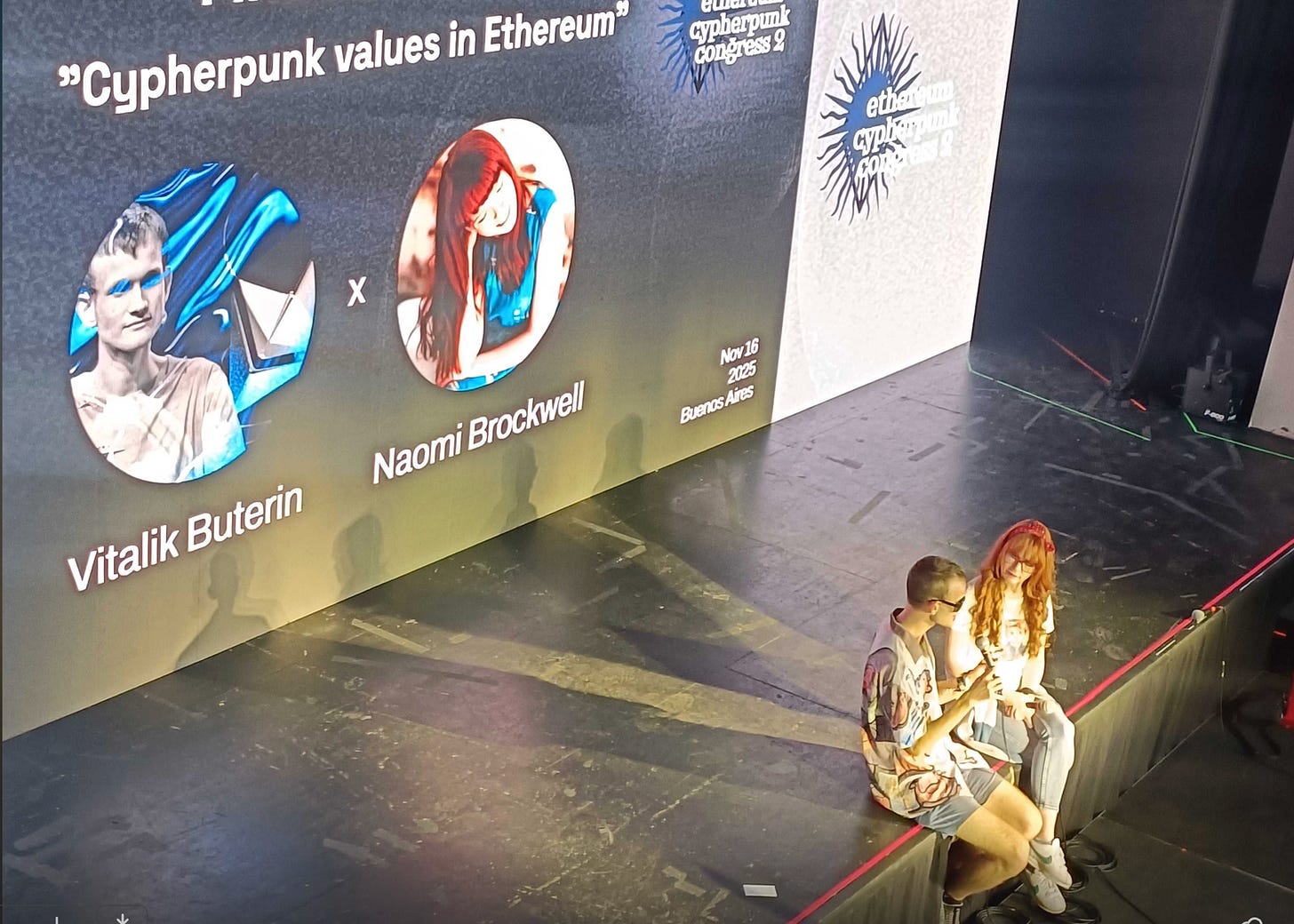

Buterin wore large, dark sunglasses as he addressed the Cypherpunk Congress. After a brief pitch for the new Kohaku framework—a suite of tools the Ethereum Foundation has built to help developers integrate privacy into crypto wallets—he sat down for a fireside chat about why the Ethereum community is so focused on privacy right now.

“[There are] barriers we’ve taken for granted—that conversations are private and money is private—each one of those is being eroded,” he said. Blockchains are arguably cypherpunk tools in that they can protect against financial surveillance by the state or other powerful groups—especially when they are paired with privacy tools like zero-knowledge proofs.

Buterin wants to be able to demonstrate that Ethereum can be useful for more than just crypto finance—for crucial things like protecting people from AI-powered mass surveillance. This would strengthen the argument that it could act as a more private (and more cypherpunk) backbone for the internet.

Tor founder Roger Dingledine remains skeptical. On the day of the congress, I ran into him on the mezzanine overlooking the main stage. When asked what he thought of the potential for crypto as a cypherpunk tool, he expressed doubt about its potential due to how its users are incentivized.

As he has repeatedly argued in the past, adding the incentive to profit from a crypto-token, or take lots of venture capital funding, could undermine Tor’s mission. His aim is to build products that keep people safe—not generate profit, he told Buterin during a fireside at a separate event the following week. At last year’s Cypherpunk Congress, he said Tor has avoided adding a crypto token “because you’d be swapping out altruism for capitalism as a building block.” Tor’s network is built through volunteer-run servers, which hide a user’s traffic through randomization loops. Dingledine says if there were a token reward to incentivize running a server, people would inevitably try to game the system. Tor runs automated checks on whether the server has the technical abilities to run a relay—if there were some way to trick the automation, it could lead to an unfair allocation of token rewards.

“I come from the free software community and the cypherpunk community, not the Silicon Valley startup world,” Dingledine said to Buterin. “We don’t have venture capital people—our goal is to build a tool that actually keeps users safe, in whatever situation they’re in. Because we’re in non-profit land we can afford to make those choices,” he said.

Buterin pushed back on the idea that a financial incentive is always a bad thing, even while he conceded that Ethereum has become a place where financial speculation is rife. “Capitalism in crypto is the ultimate double-edged sword,” Buterin said. While huge institutions with lots of money “make the numbers go up,” if that kind of investment had never happened “we would not have had the funding to develop [things like] zero-knowledge proofs,” he said.

While the power of the original cypherpunk movement lay in part in its uncompromising stance, by the end of the day, I had come to understand neo-cypherpunkism as a mantra that values the middle ground. From Soleimani’s protected lake to Buterin’s nod at market economics, both had shown that the development of new privacy tools come with trade-offs. And while crypto grapples with its image problem, these choices have the potential to make privacy accessible beyond the walls of an underground club—with a higher chance of converting the masses.

Follow us on Twitter and Bluesky—or get corporate with us on LinkedIn.