Welcome to the jungle

We got fun and on-chain games

Greetings, traveler. Whether by luck, skill, or intervention of the divine fates themselves, you find yourself at our humble tavern. You have traversed the World’s grime, weathered its swindlers and knaves; you are weary. Yet you still thirst, thirst for knowledge that runs pure as the coolest streams—knowledge that will revive you, prepare you for the challenges to come. This we have in ample supply, and we bid you welcome.

This is Glitch.

In this issue:

What’s good for The Goose

On-chain game theory

The Zuzalu Zoo

1. Sotheby’s blockbuster NFT sale ≠ crypto legitimacy. As the liquidation of the disgraced crypto hedge fund Three Arrow Capital’s portfolio kicks into high gear, a number of NFTs have made their way to the block at the centuries-old auction house Sotheby’s.

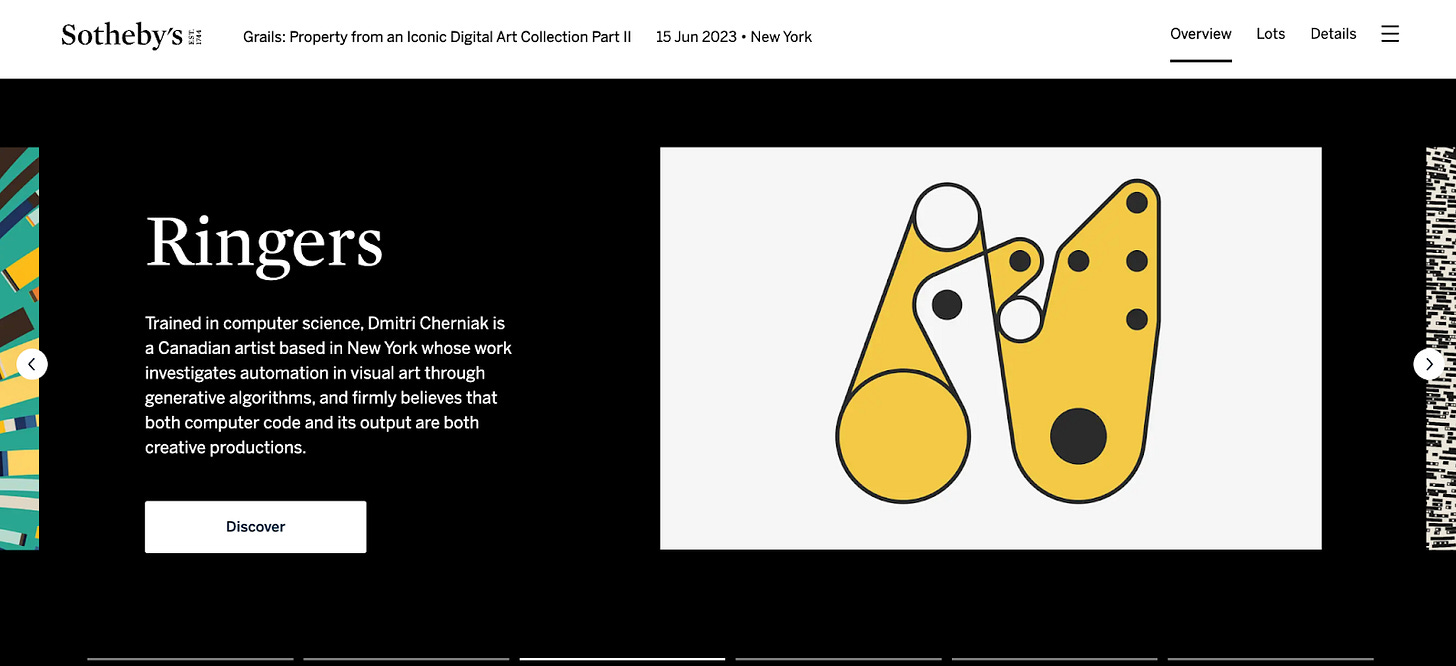

The digital items, which are considered to be so rare they were dubbed ‘grails’ by the NFT mafia, include notable lots such as generative art darling Dmitri Cherniak’s Ringers #879 (also called “The Golden Goose”), CryptoPunks, and a Chromie Squiggle. Bid up in the market in the bull run of 2021, the collections on offer have become examples of why NFT art is “valuable.” The sale has already raised millions, with Sotheby’s creaming off its usual 10% commission.

On the block last week was the Goose, the crown jewel of the collection, which sold for $6.2m—a tidy sum for a .jpeg (and outstripping the $5.8m 3AC founders Kyle Davies and Su Zhu paid for it in the first place).

Sotheby’s sale blurb called the works that were selected “some of the rarest and most important” in the “Contemporary Digital Art and Generative Era.” But how did the institution actually come to that conclusion? We are talking about digital files of the kind whose value seems to have manifested out of the ether just a few years ago. Were they just taking cues from Davies and Zhu? Who is to say what is important as an art work, anyway?

Sotheby's appears to want everyone to believe they are the arbiters of an artwork's importance. “If we are listing it, then let me tell you, rich person, it is worth your time. And money. Just money, really. Which you can give to us now. Thanks.”

What's fascinating about this particular tie-up is it's hard to tell who is playing who. Is Sotheby's winning this transaction by selling otherwise worthless digital trinkets to wealthy rubes? Or are the believers in NFTs winning, co-opting Sotheby's considerable clout as an auctioneer of priceless art to confer legitimacy on a medium that still garners a lot of skepticism?

No matter your opinion, pawning off these assets seems like an icky choice at best. When 3AC went down in flames, it took millions worth of ordinary people's savings with it. (Meanwhile, the New York Times caught up with the founders as they lounged on a beach in Bali.)

As for the last time Sotheby’s appeared to be caught with its hand in the cookie jar of amoral profiteering, we have to look far back in the mists of time to … January, when a Maori tribe in New Zealand had to ask Sotheby’s for the return of ancestral treasures listed for sale.

What remains is the fact that Sotheby’s continued interest in NFTs is a signal for the future of digital art. Maybe it is worth the risk for the auction house to be affiliated with what Davies and Zhu did, lending legitimacy in return for a chance to up its own digital artistic cache. If there’s a common thread to be pulled from the works being hawked so far, it’s that the chosen pieces all ride off the back of the latest wave of generative and AI art hype. And apparently, that wave isn’t quite over yet. —Lucy Harley-McKeown

2. WTF is an “autonomous world”? The last game world that Emerson and Morris Hsieh built died suddenly at the hands of a corporate overlord.

In late 2021, the brothers built a custom Minecraft server called Critterz. The world had its own currency, and its land and buildings were Ethereum NFTs. Critterz became a bustling economy where enterprising builders were making thousands of real dollars a month. Then, in the summer of 2022, came a stunning blow from Microsoft-owned Mojang Studios: “Blockchain technologies are not permitted inside our Minecraft client and server applications nor may they be utilized to create NFT associated with any in-game content.”

Since then, the Hsieh brothers have become determined to make a game that can’t be killed—or even owned.

Their goal is to make a game whose logic and rules are encoded in a blockchain, not a corporate server. And to make it fun in a way that takes advantage of the blockchain network’s unique capabilities.

According to the Hsiehs, a crucial ingredient is what they call a “sovereign game economy,” in which no one would have the power to unilaterally change the value of a resource or item. That’s what the brothers envision for the factory-themed game they are building, called Primodium.

The Hsiehs are one of dozens of teams building on-chain games. As I wrote recently in Wired, some have started calling these games “autonomous worlds,” in part because they can be set up so that they can’t be shut down without shutting down the entire blockchain network. No one has made a real one yet, though, and Primodium is the fastest out of the gate in the race to change that.

Early iterations are running on a test network, where the Hsiehs are collecting data and player feedback. The game launched just over a month ago, and the brothers have spent the first several weeks fixing bugs and tweaking the gameplay. Their first priority was building a new onboarding system. At first, newbies were dropped in the middle of the sprawling map and had to figure out how to play using a guide that quickly became outdated. Now they are greeted by a character named Colonel Langeman, who runs them through the basics.

The Hsiehs tell me they have now turned their attention to gameplay, with a particular focus on making Primodium feel more like Age of Empires, where players are encouraged to develop and defend bases. As with Minecraft, many people already find the basic dynamics of the game fun; no need to reinvent the wheel.

On-chain game designers are surely trying to reinvent something, though. The Hsiehs know it’s on them to show us exactly what that is. —Mike Orcutt

3. The “Network State” Goes LARP in Montenegro (Feat. Longevity): When Balaji Srinivasan, the investor, think-boi, and former CTO of Coinbase, released his manifesto, entitled “The Network State,” on July 4, 2022, it was only a matter of time before someone tried to make it happen in real life.

And lo, it has come to pass. With some help from Vitalik Buterin, a tiny sliver of resort space on Montenegro’s Adriatic coast recently became the setting for a live experiment meant to end the need for countries and help people live for 5,000 years. Running for a two-month stretch between March and May, Zuzalu, as it was dubbed, was a “pop-up city community” with “longevity at its heart,” bringing together 200 permanent residents and about 800 temps to learn, discuss, create, and hack, with lectures on topics like “synthetic biology,” “technology for privacy,” “public goods,” “human longevity,” and “governance.” According to the event pages, participants were encouraged to see the experience like “living on a college campus with a 10% workload” with a focus on “plant(ing) the seeds for what can become a new sovereign zone.” It was also about bringing together various royalty of the Ethereum extended universe; a nifty example of what Ethereum people like to call the ‘social layer.’ Oh, and there were DJ sets by Grimes.

The event was sponsored by VitaDAO, a “decentralized science” DAO focused on “human longevity” research, that raised a $4.1 million funding round in January led by Pfizer. The round also included an investment from Balaji, and past investments from Vitalik, for whom longevity appears to be a pet project (he once tweeted that if we deal with the underlying causes of aging, life expectancy shoots up to ~5,000 years). The Zuzalu community claims to be “already researching a permanent village,” with plans to build a “v0/beta version of a Longevity Network State.”

What in the actual fuck does this gibberish mean? Glad you asked.

The concept of the network state is that, in an age of social media and magic internet money, it’s possible (and even desirable) to create a country online built around a shared set of cultural values that transcend the boundaries of present-day nation-states—say, an interest in extending the duration of human life. Basically, if you’re a “network statist,” you think that our current countries suck and they’re doing a bad job at tech and pretty much everything else (which, fair). So instead of working within the existing systems to, say, reform or update them, the thinking goes that it would be better to create a new one that hacks its way to legitimacy—and power!—by proving the thesis that new countries can be created in the cloud.

Zuzalu appears to be attempting this in a few ways—LARPing a number of tools and ideas originally mentioned in Balaji’s book. For one, to enter the village, residents have to use their Zuzalu passport, or “Zu-Pass,” which purportedly uses zero-knowledge proofs to prove Zuzalu citizenship without revealing who they are. Zuzalu has also created a “plural communication channel (PCC)”, which describes itself as a “playful first step towards decentralized agenda setting, question curation and community deliberation through collusion-resistant quadratic voting.”

Residents could also choose the “health track” at Zuzalu, and become a lab rat (err…first adopter?) for longevity research, which included a specialized meal plan, a workout itinerary, and a number of biomarker tests that “track changes based on various scientific interventions.” The event’s Notion page includes a section called “Longevity Jurisdiction/Innovation Zone,” which states among its aims that by the end of the conference participants will be “carrying a common message of delegitimization of the current system” while agreeing on a “moral innovation.” That’s Balaji’s term for a principle that justifies, in one commandment, the existence of a network state. In his words, “communities are causes first, companies second.” (And yes, to Balaji, everything is a company).

So, what does a “v0/beta version of a Longevity Network State” look like in practice? For now, apparently, it’s a bunch of nerds getting together in a fancy resort to rub shoulders, listen to Grimes, play with some new toys, and talk about living longer than a glacier. Nalin Bhardwaj, a cryptography researcher at 0xPARC who attended the event, told me he thought of it mainly as a networking opportunity—a chance for tech-types to shmooze and play houseguest. But that’s just for now.

To my mind, the right frame for Zuzalu—along with other network state tossups like Praxis or Prospera with subterranean ties to Peter Thiel (for a full list, scan the graphic below)—is the emergence of Socialist Workers Movements in Europe (and Russia, in particular) in the late 19th century, which paved the way for the rise of communism. If you look back at the writings of the would-be communist party leaders in the 1880’s, they, too, look like bumbling idiots, peddling utopian dreck that seems naive and foolish; arguments that loosely cohere into a vision for a new society. But then, forty years later, they suddenly found themselves at the helm of a state. It didn’t end well, but it wasn’t because their ideas never caught on.

Ok, so it’s a bit of a stretch. And I know what you’re thinking: These tech libertarian types are terrified of communism. In fact, it seems that they’re trying to build the opposite. My point isn’t that Balaji is a closet socialist. It’s that the political alchemy surrounding this experiment, and others like it, is potent. Zany as it appears, it shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand.

For the foreseeable future, projects like Zuzalu will remain innocuous and dorky—far fetched enough to be easily ignored. But give it some time—5 years, 20 years, 40 years—and the idea that countries should be social networks first (and not random blobs of mostly stolen land, as they are now), or that money should be digital (and not piles of paper covered with the visages of dead people), or that death is not inevitable (and maybe we can do something about it), or that computing power should be distributed (and not housed in giant warehouses owned by like three people), might not seem quite as looney.

And given a cohort of quasi-stateless billionaires looking for low-tax ways to park their money, funding a bunch of developers coding the rails of the new internet, plus plenty of political dissatisfaction and rising populism and inequality and…you get the picture…the idea that this group might come up with something disruptive (and I mean this in the literal sense of the word), might not be so ludicrous. On a long enough timeline, in fact, it might seem like something close to common sense.

That doesn’t mean I’m not worried. There is a lot in the network statists' plans worth criticizing, even mocking—much of it just plain lazy thinking from a bunch of super-privileged techno-elites. But while Balaji & co may not be proven right, it's worth considering whether they might not be entirely wrong, either. If I were a betting man I’d say there’s something abrew in Zuzalu (a name randomly generated by AI, by the way). If not now, then soon. —Sam Venis

Follow us on Twitter, if you want: @ProjectGlitch_